Published Wedensday, December 25, 1996

Air Show

Admirals' blimp breaks ice

Ticket, coupon drops make it a fan favorite

|

|

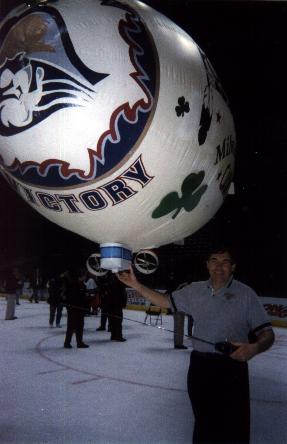

Bruce Luetzow (left) helps flight test Admirals

Victory, a blimp flown

during breaks in Milwaukee Admirals games at the Bradley

Center.

Photo by Jeff Phelps, Journal Sentinel Staff

Photographer |

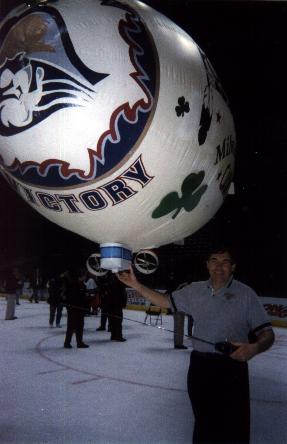

Scott Fisher next to the Milwaukee Admiral

Victory (Taken March 17, 1999) |

BY TIM NORRIS

of the Journal Sentinel Staff

Heads up, Milwaukee Admirals fans! Those overgrown adolescents and their

tantalizing toy are unleashing another paper rain.

Feather left, bank right. From a folding chair on the mezzanine

overlooking the Bradley Center ice, Scott Fisher can't contain himself.

"Now watch this!" he says. "Watch this!"

A worm wire turns, tickets and coupons tumble. Flutter! Flap! Wild

scramble!

The blimp and its boys strike again.

Some 20 minutes at a time, three or four times a night, 42 game nights a

year, the pilots of a mini-blimp that fans have named Admirals Victory

seize the center's inner spaces. Pre-game, between periods, post-game

throughout the home hockey season, the blimp annihilates lulls.

On this weekday night, before a game with the Manitoba Moose, the big

question backstage is whether it will annihilate itself.

Bruce Luetzow is flight-testing the airship in the open alcove just then,

and all at once he pulls it back inside. "No vectors!" he yells to Fisher.

"No tail!"

Three wood propellers 5 inches long, two on the sides to drive the ship

and one on the tail to steer it, have just dropped dead. Show time in 5

minutes!

With the exuberance (and terror) of youth, the men scramble to the repair.

With one hand, Fisher pulls the white bag of rubberized nylon, filled to

15 feet long and 6 feet wide with helium, into the makeshift hangar

beneath the seats.

What's the trouble? Tangled connecting wires? Radio receivers on the

fritz? That's it, dead battery! Fisher grabs a fresh pack (they always

keep extras charged) and slaps it into the gondola, near the small motor.

Then, radio in hand, he heads for a folding chair in an alcove, halfway up

the east side.

To Strauss' "Blue Danube" waltz, the blimp lifts into the lights. Heads

tilt. Eyes turn. Arms reach. Fisher, installed in his chair, gets ready

for strafing runs. "Watch this!" he says.

The blimp teases a pursuing pack of teenagers, then zips away across the

ice to drop tickets into a young couple's laps. Then it races the Zamboni.

Hardly anyone notices Fisher working the controls. He noses the blimp

toward the net, taking it inches from the ice, hoping to surprise an

attendant. But an indoor wind he calls the Bradley breeze fishtails the

blimp, and he guns it upward again.

A boat whistle blows, announcing game time, and the two men flash hand

signals. Luetzow takes control from the south tunnel and guides the blimp

back toward its mooring. "If he makes a good landing," Fisher says, "I

keep the radio antenna up and pretend I did it."

Luetzow cozies the blimp's 6-foot width into a space only 4 feet wider.

Perfect! A few people applaud.

Nobody describes the pilots with the words "arrested development." Hey big

little boys just wanna have fuh-un!

But Fisher will admit that part of them never has caved in to adulthood.

Fisher and Luetzow and, sometimes, Jim Wirt, a world-class flier of

four-string competition kites, say they've never lost that childhood dream

of flying in the clouds, free of earthly cares.

Buzzing the seats is a good substitute.

Under wider skies, Fisher and Luetzow pilot full-size planes, Cessnas,

single-engine; they met, in fact, among the aircraft at Mitchell Field.

(Wirt came into the picture through Fisher's first love, kites). Most of

the time, they work for a living.

As business, uh, men, they've seen their share of serious. Like,

daily. Payrolls and benefits, taxes, inventory, rent,ordering, delivering,

buying, selling, deadlines, deadlines, deadlines.

Get the radio control consoles' twin joy sticks between thumb and

forefinger, though, they say, and the years and the worries fall away.

Right joystick: power, up for rise and down for drop; side-to-side, rudder

(direction). Left joystick: up for forward and down for back,

side-to-side, the worm wire. How about a power drop at the kid with the

buzz cut?

Into their third season, the men feel so comfortable handling the radio

controls they often become One with the Blimp. "It gets to be like driving

a car," Fisher says. "You don't think about changing lanes or turning

corners; you just do it."

But the pilots also can become One with a Glitch.

A twisted wire can ground the ship. A backward creep on the worm wire can

jam the works. And the blimp moves more with the feel of a boat than a

car. It can be buffeted by a crosswind, the indoor breeze born of body

heat and ventilation, whirling counter-clockwise through the Bradley

Center. Cool ice, thickening the helium, pulls the blimp down; hot lights,

expanding the gas, push it up.

"You add a little lead for ballast to make sure it drops, just in case,"

Fisher says. "You don't want to pick it off the ceiling."

The blimp's shaky maiden voyages in 1994-'95 are close in Fisher's memory.

"He'd never done it before, so there were no procedures," Luetzow says.

"He literally took it out of the box and inflated it. On the night of the

grand opening, with the place packed with people, he survived somehow. But

ask him how many times he had to go to the boys room before he took

off."

After the first year, Luetzow helped Fisher set performance standards,

assembling a booklet with procedures. They replaced awkward walkie-talkies

with a two stick radio controller from a toy store. They mastered the

aerodynamics.

Sneak around backstage, down in that south tunnel, beyond the goal and

behind the curtain kept closed during games, infact, and you might even

learn a little science.

F'rinstance, Luetzow says, the blimp needs exactly 1 cubic foot of helium

to lift one ounce. Capacity? Not counting air leaking in around seams, 200

cubic feet, meaning it could hall about 13 pounds. Should take care of a

few dozen tickets and a couple of plastic parachutists.

Or consider that a radio signal will not penetrate a scoreboard. "We

learned that the hard way," Luetzow says.

Worst case? They lose control, shut off the propellers and the blimp

settles into the crowd in a soft bump. Best case? "Just watch peoples's

faces as it moves over the heads," Fisher says. Wide eyes. Gawks. Total

attention.

If the blimp leaves the thinnest vapor trail of commerce, Fisher doesn't

apologize. His own Gift of Wings shops, in Mayfair Mall, on the Milwaukee

lakefront and in Minnesota's Mall of America, sell all kinds of toys that

fly.

One product is a 3-foot remote-controlled blimp; his demonstrations of it

around Mayfair Mall led to the hockey gig. The idea for Admirals Victory,

in fact, came from Lloyd and Jane Pettit, benefactors of the Bradley

Center, who saw a similar ship in Phoenix three years ago. A staff member

recommended Fisher.

Knowing that a victory can pump up a crowd but a loss can knock the air

out, knowing that some games sag a little and that a hundred high-tech

hucksters tug at what they call "the entertainment dollar," sports

franchises try to transform games into family events.

Fisher, One with the Philosophy, puts it this way: "As long as the fans

have a good time, win or lose, they'll come back."

The blimp obliges. Like most miniatures of mighty machines of transport,

the Admrials airship is, well, cute, especially when it spins a

full turn or sashays backward, or when it nudges the attendant setting up

the nets or busses the glass in front of a fan.

Action transforms it into a cartoon character. "The Admirals don't need a

mascot," Fisher says. "They have the blimp."

Children seem to agree. One of the oversized adolescent pilots, Luetzow

has brough his actual little girls, Kim, 8 and Ashley, 5. They are

showing remarkable maturity, although Ashley does skip in the hall

a little. "They love being with us on a game night," their father says.

"The blimp is just like a magnet for them."

Parenthood might age a man, too, but Luetzow, who runs his own plastics

business, seems to have taken a pass on that part. For intermission

between the first and second periods, he climbs to a coach's empty seat in

the open press box.

"I'll hop it across the ice now," he says. "Ready? Don't know if I'm still

over the ice." Tickets flutter neatly into the first two rows. "Yeah!" He

dances the blimp down the rink.

The men dream, these days, of creating a deer-shaped ship for the

basketball Bucks; even of a Brewers blimp inside the new Miller Park. "We

could get one 25 feet long," Fisher says. "Just think. You could advertise

on it!"

In the Bradley Center's more modest realm, the home team takes the Moose

into overtime, then into an overtime shootout, where the good guys win,

5-4. Fishe untethers Admirals Victory for its extra flight.

"Watch this!" he says. Everybody does.

Back to the Admirals Homepage

Back to the Admirals Homepage

Copyright 1996, The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. All Rights Reserved.

Back to the Admirals Homepage

Back to the Admirals Homepage